On the Edge of Seeing

录入时间: 2012-03-12

For Long Beini

Andrew Brewerton

Colour iridescence in most flowers occurs at the ultra-violet range of the light spectrum, visible to the compound eyes of insects but invisible to the human eye. This petal iridescence depends not on colour pigment but upon surface structure, in which colour tones alter according to the angle from which the flower is viewed.

This is also true of the brilliant iridescence of certain moths and butterflies, whose tiny wing scales display the most astonishingly multi-layered, microscopic structures: “among the most complicated extra-cellular structures that are manufactured by a single cell”.

The English word ‘iridescent’ derives from iris, in classical Greek mythology the messenger of the gods, whose earthly sign was the rainbow. Normal human colour vision is indeed limited to the rainbow spectrum, those electromagnetic wavelengths that border upon ultraviolet and infrared, occurring in the range of c.400–700nm, that can be distinguished by the rod and cone cell receptors that make up the physical surface of the human retina.

Where honeybees have evolved trichromatic colour vision which is insensitive to red but sensitive to ultraviolet, human trichromatic vision is mediated by three types of colour receptors containing pigments with different spectral sensitivities, capable of absorbing light at long, medium and short wavelengths, which approximate to orange-red, green-yellow, and blue, respectively.

These three retinal primaries differ from the rainbow primary colours (red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet) and from painters’ primaries (red, yellow and blue), and

the fact that the retina has its own set of primaries is a very deep mystery.

In reduced light, colour sensation in human vision migrates towards the short ‘blue’ wavelength and, in low light, rod cells in the human eye can distinguish 500 shades of gray. The human retina hosts 120 million rod cells for night vision, and 8 million colour-sensitive cone cells that have evolved and adapted for daylight conditions , in which we can distinguish millions of different colours, for most of which we have no names.

Languages that have only three basic colour terms always have black, white, and red. Those with four add yellow or green. Those with five have both yellow and green.

Such astonishing consistency in human language may well be true as an index of universal colour classification, but our experience of colour can never be confined by language, and is infinitely variable in terms of the sensation, colour hue, luminosity (intensity), and colour saturation. Colour qualities and characteristics vary on scales of brightness and darkness, wet and dry, surface texture and gloss, freshness and dessication, liquid, earth and air bodies, indelibility and fadedness, roughness and smoothness etc. etc. Every new combination of these qualities is a new experience, a fresh sensation evoking an aesthetic response.

These colour qualities are further complicated by our physiology, our technologies and cultures, and even via synaesthetic resonance with other senses. Sensation varies between individuals. For example (though I am sure you will disagree!) it seems perfectly clear to me that the number 1 is white, 2 is yellow, 3 is green, 4 is orange, 5 is blue, 6 is pink, 7 is violet, 8 is red, 9 is brown, and 10 is most definitely black. Don’t ask me why.

But why, you may ask, in a brief text for Long Beini on her new works in oil on canvas, is this writer so deliberately detained, and in such detail, by the optics of light and the human physiology of colour perception?

Because the impulse for this canvases, their subject, their making, and the presence or sensation of the finished work, is so very finely poised between the experiences of seeing and of not-seeing. For these paintings were made after some years of not-painting, immediately following an eye infection. “It wasn’t serious” said the artist, “but I couldn’t see for a week”.

The subject matter, mostly involving the human figure, is almost arbitrary. The real impulse for this work was the attraction of ‘a small point of color or a certain atmosphere’, that caught the painter’s eye amid a range of photographs and images torn from fashion magazines. The real subject is the impulse to colour, and the experience of the medium of colour pigment and its physical application to the stretched canvas:

I use the canvas as the color palette, to crush the oil directly on the canvas, and using the pencil, fork, stub or paper as the brushes.

This is the bodily act of painting: its physical, gestural, emotional and performative dimensions; its duration in time, in the act of looking and reflecting; its tactile and sensory involvement in the materials of oil paint, white spirit thinners, canvas fabric, and light.

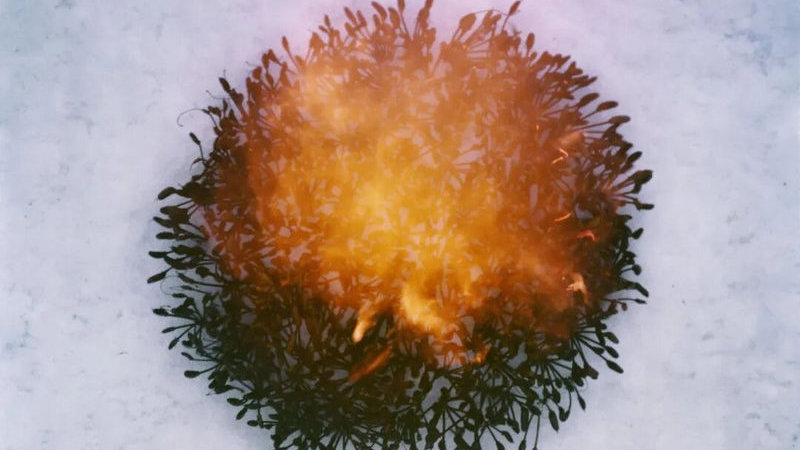

Pina Bausch, the modern dance choreographer who died in June, once said that she was not interested in how her dancers moved, but in what moved them. And this is the unspoken energy that these paintings evoke, on the edge of seeing and not-seeing. Each in its complex and beautiful, layered and structured colour surface, every bit as fragile and brilliant as a hibiscus flower. As a butterfly wing.

(Andrew Brewerton is an English poet and writer on contemporary art, and

an Honorary Professor of Fine Art at Shanghai University since 2000. He

was Principal of Dartington College of Arts from 2004-8, and has held a number

of academic and public appointments: including Professorships at the

Universities of Wolverhampton and Plymouth; as national board member of Arts

Council England and as Vice-Chair of the Prime Minister’s Advisory Group on

Higher Education. )

开放时间:每周二至周日9:00-17:00(逢周一闭馆)

每日16:30停止入场

地址:广东省广州市越秀区二沙岛烟雨路38号

咨询电话:020-87351468

预约观展:

-

广州 影像三年展 2025 Guangzhou Image Triennial 2025 ...